Back to Virtual Studio

Back to Voices

Nora Thompson

Five years ago I was Eiko's student at Wesleyan University. I was learning to see my body as a landscape, to be popcorn or marshmallow or maggot, while also reading pages and pages of atomic bomb literature. We often were shocked by the atrocities we read about, prompted to say "I can't imagine" again and again. Eiko insisted that instead we try to imagine.

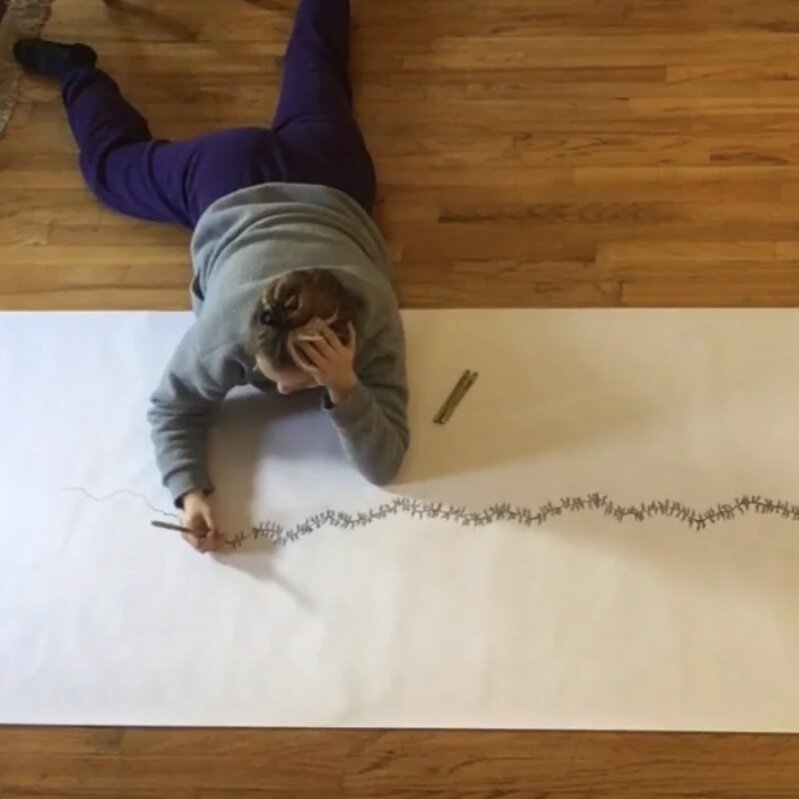

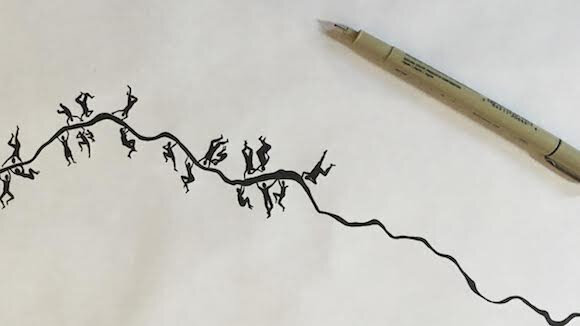

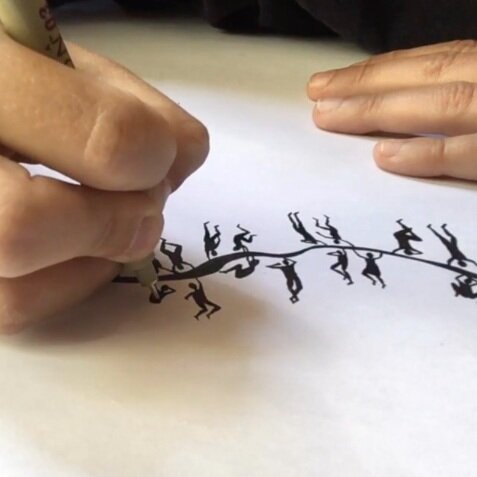

For my final project, I took on her call to imagine. Inspired by a quote from Kyoko Hayashi describing people desperate for water in the aftermath of the atomic bomb--“There was a kind of intimacy about this scene of river and people, as if the running water were a giant centipede and the people its legs"--I created a landscape of bodies, small figures with their heads towards a river, that continuously grows. Titled, Centipede, I aimed to explore how large numbers like death tolls and statistics dehumanize their subjects while also attempting to enliven each lost individual. Centipede was first performed at Wesleyan University’s Olin Library for nine hours over five days.

After graduating, I continued to work with Eiko helping her with social media, communications, website troubleshooting, but also with reflecting and responding to her work. She continued to invite me to extend the work of Centipede as its relevance kept emerging: I performed at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City for a an event memorializing the fifth anniversary of the Fukushima disaster curated by Eiko in 2016 (for four hours), at the New York Buddhist Church for their service remembering Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 2017 (for two hours), and at an event, "Facing Disaster," in which Eiko spoke about Fukushima at Wesleyan in 2018 (for two hours). Centipede's figures had shifted to act as a conduit for imagination not only for atomic bomb victims but also for those affected by the Fukushima disasters. My idea of loss expanded past death to include those who were forced to evacuate, those whose homes were irradiated, those whose pain and loss were subsumed by a narrative of disaster.

Photo by Ria Shibayama

So, it is apt that Eiko asked me to reconsider the drawing in the midst of this pandemic. Of course, this effort to empathize and imagine is relevant for any event in which human lives and deaths get abstracted. I thought, at first, of course.

But, I feel some hesitation in resuming the drawing. So far, this process has been to understand the scale of lives lost in the past, due to an event that is (largely) over. So far, this process has been an effort to collapse distance and bring the far away right under my nose.

But this pandemic is here and now. It is so literally under my nose, in the form of a mask made out of a tank-top and hair elastics. I am in New York City, "the epicenter." I hear the sirens constantly. My roommate probably had it. My partner might have it right now. I probably have it, had it, will have it. It is so here and now that I can just say "it," and we all know.

This is different because I am living inside it, through it, among it. But it is the same too. While I am holed up in my partner's apartment, safe with food, medicine, television, and a puzzle, I can't see what those sirens really mean. Friends from other cities call and ask "is it really as bad as it looks in New York City?" I don't know what to say. My visual experience is of the cherry blossoms in our backyard, cooking and doing dishes and cooking and doing dishes again, my computer screen. I only see a five-block radius of brownstones and small apartment buildings and closed storefronts, masked neighbors walking dogs. It's eerie, but it is not a nightmare. I have yet to see the death. I have yet to know someone in the hospital.

I am inside of this slow, terrifying disaster, but also protected from it by my walls, my whiteness, my wealth, my steady job. I don't know anyone who has died from it yet. Reporting is coming out that black people are disproportionately affected, disproportionately dying. This system that oppresses, of course, oppresses further in crisis.

They say 100,000 to 200,000 Americans will die from it this year. If someone says, one more time, that "everybody dies sometime anyways" I will fucking scream. Eiko has instilled in me this belief that everyone deserves their own death--a personal death. When we count deaths in such numbers, we depersonalize them. This is the reality of mass violence, of genocides, and even public health crises. We must face the truth that these deaths are not like others. These deaths have to happen in isolation in hospitals. These deaths don't get funerals. Some of these deaths will be due to rationing care, ventilators, beds. Some deaths will be considered more inevitable than others--eugenics has and will rear its head. Do these numbers count those who will die because of anti-Asian violence? Do these numbers count those who may take their lives when faced with isolation? Do these numbers count those who are trapped inside with abusive partners?

So, this time, I am not counting up towards some finite number. I cannot count because the loss is still evolving, and I feel certain that so much loss and pain will not be "officially" counted. This time, I will lay down and draw to connect with my current reality, to empathize with those who passed alone, to imagine those who face more danger than me now. I will outline each human with care and imagine the pain that I can't see outside my apartment now. I will lay down and draw not only to focus on the individuals and the now, but also to keep learning how to be with and support a collective when we have to be spread apart.

See more of Nora's work at www.norarainethompson.org

Read Nora’s responses to other works in Virtual Studio here.